[ad_1]

[Photograph: Vicky Wasik]

We’re all for the skill and dedication it takes to brew a rich, flavorful cup of pour-over coffee. But on a Tuesday morning, when time is short and a caffeine headache is just a few hours away, it would be nice to know you can pull the carafe from an automatic coffee maker and actually enjoy the stuff you’re going to pour into a cup. All too often, outsourcing coffee-making to a machine means trading convenience for taste.

Our goal was to find well-designed, automatic-drip coffee makers that deliver great tasting coffee. We tested 15 models, ranging from about $20 to $310, and put them through rounds of tastings and other evaluations to find the ones that performed the best.

Our Favorites, at a Glance

The Best Simple Coffee Maker: Bonavita 8-Cup Carafe Coffee Brewer

The Bonavita is one of the faster models we tested, and it earned high scores in nearly all of our tastings. A single switch governs all of its operations, making the brewing process incredibly simple. The only design knock is the brew basket: It sits directly on top of the open stainless-steel carafe, which means you have to fully remove it and deal with the wet grounds before you can enjoy a cup of coffee (on the flip side, maybe that discourages the bad habit of leaving the stale, spent grounds in the machine for hours on end).

The Best for Control Freaks: Breville Precision Brewer

While you can get it brewing with just the push of a button, the Breville offers layer upon layer of fine-tuned control for the coffee geek who wants to tweak brew variables. Finishing near the top of our taste tests, this spendy machine allows you to control brew water temperature, time, and the blooming phase. It also can make cold brew, and it’s compatible with popular pour-over devices like the Hario V60 and Kalita Wave.

The Best Budget Coffee Maker: Braun Brew Sense Drip Coffee Maker

While we tested machines that are five times pricier than the Braun, its performance in taste tests, its ease of use, and its wallet-friendly price pushed it to the head of the pack.

The Criteria: What We Look for in a Great Coffee Maker

The most important aspect of a coffee maker is how well it brews coffee. So, what makes for a good cup of coffee? Well, that’s very subjective. Some drinkers like dark roasts, while others lean toward fruity, lighter coffees. A lot of coffee drinkers enjoy a morning cup strong enough to crack the glaze off their eyes, while others brew theirs as weak as tea. Then there is texture: are you more of a gritty French press–style coffee drinker, or do you want a clear brew with every last trace of the grounds filtered out? While even professionals can’t fully agree on what “good coffee” is, they at least have some criteria that can help us toward a definition. A good cup of coffee is, in essence, one that has successfully extracted the solubles you want out of the bean, while leaving behind most of the ones you don’t. Factoring into the success of that extraction is brew time and temperature, the blooming phase, water turbulence, grind size, the beans themselves, and more. It’s a complex process with a dizzying array of variables.

Given all of those variables, it’s difficult for any evaluation to account for each, though we tried by doing the following: we conducted blind taste tests with multiple tasters, both pros and daily coffee drinkers; we tested coffee beans of varying styles, origins, and quality; we measured some empirical markers like total dissolved solids (more on this below); and we examined water temperature, brew time, and other factors that can be helpful in at least indirectly assessing brew quality.

No matter what, using an automatic coffee machine forces you to relinquish some level of control. With simple machines, you press one switch and hope it delivers a good cup of coffee. With the more advanced coffee makers, you can specify some brewing parameters, but you still have to trust the machine is executing them correctly. You really never have a say in some coffee-brewing aspects like showerhead design, how evenly the grounds are wet, or the turbulence of the water in the coffee bed. And there is no way to make in-the-moment adjustments like pouring water faster or slower to influence the speed of the brew process.

Every coffee machine should make a decently good cup of joe with a button touch (or two), and be intuitive enough for family and friends to use without having to ask for help. Ideally, we’re only turning to the manual if we want to learn about more complex features for those machines that offer them. A good coffee machine should be easy to clean, too: A funky buildup of dried-up coffee or crusty grounds isn’t going to help your next brew taste better.

All coffee makers do the same thing—pull water from a reservoir, heat it, and then distribute the water over the grounds in the brew basket through a showerhead. When the properly heated water passes through beans ground to the correct size, you should extract the desirable flavor and aroma compounds from the roasted coffee, while leaving unwanted flavors behind.

To help brew more flavorful coffee, some manufacturers build a “bloom cycle” (sometimes called pre-infusion) into these machines. During the bloom phase, the brewer sprays a small amount of hot water onto the coffee to release the carbon dioxide locked inside the grounds. With the gas gone, the rest of the brew water, which follows about 30 to 60 seconds after the bloom, has an easier time extracting flavor. While this feature is usually found in higher-priced machines (and three out of four of our winners), some of the less expensive, non-blooming models we tested made a good cup of coffee without it. There are machines that, while they don’t claim to have a bloom phase, deliver a similar action by dispensing the brew water over the grounds in pulses, waiting several seconds between each batch of hot water.

During our research we turned to the coffee pros at the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA), an industry organization with a program that certifies residential coffee machines. Coffee Science Manager Emma Sage, who runs the SCAA’s Certified Home Brewer program, described for us the nine areas (opens a PDF) of a manufacturer’s coffee machine they evaluate. While they look at, and develop standards for, things like brew time and temperature, and certify machines that meet certain design parameters, they don’t run taste tests. Currently, about 18 models carry the certification and the prices for an SCAA-approved coffee machine run from about $130 to nearly $350. Since we were curious about whether spending top dollar gets you a better cup of coffee, we included many of these certified models in our tests, along with popular coffee makers according to Amazon. We cross-referenced reviews on, America’s Test Kitchen (subscription required), The Wirecutter, and Good Housekeeping.

We also worked with Christopher Malarick, a trainer and educator from Joe Coffee, and Matt Banbury, the New York regional manager at Counter Culture Coffee. These coffee experts, along with Serious Eats staffers (all daily coffee drinkers), were on hand for rounds of blind tastings and other testing.

A Note About Cup Capacity and Coffee Ratios

While researching coffee machines, we came across models that describe their capacity in cups or ounces. The US government considers a cup to be eight ounces (PDF), but coffee maker manufacturers don’t always follow this. Depending on the manufacturer, a “cup” can range from four to six ounces, which makes it difficult if you’re shopping by max capacity.

All the manufactures include a recipe for brewing coffee, with each calling for different amounts and ratios. But we wanted to make the same amount of coffee in each machine during each test to control as many variables as possible. For consistency and accuracy, we used a scale, instead of volume measurements that many people rely on at home. We settled on a 16:1 (by weight) water-to-coffee ratio for our tests, and weighed both on our favorite kitchen scale.

The Testing

Taste Tests

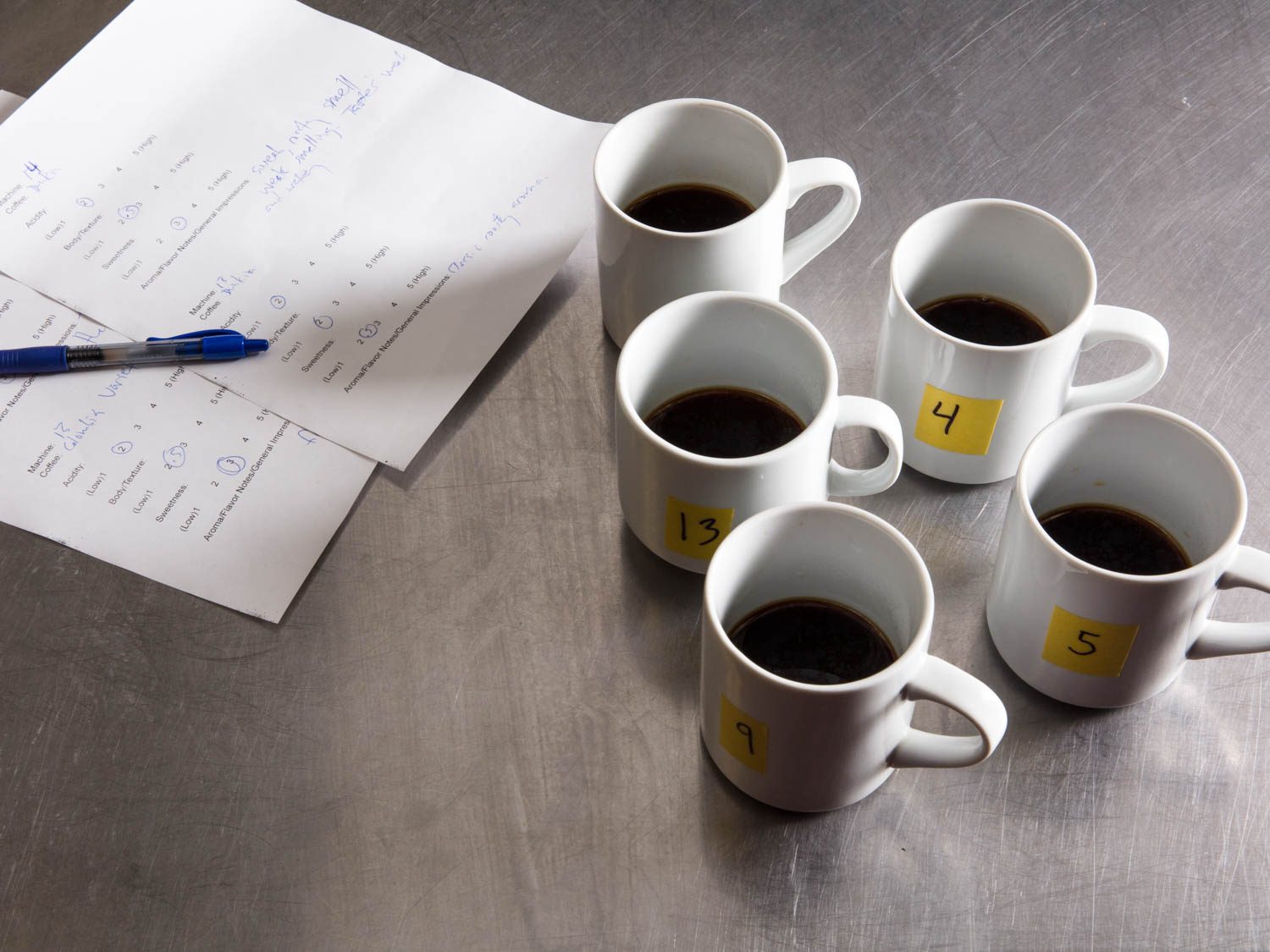

We had coffee experts, and Serious Eats staffers, participate in several rounds of blind taste tests.

Coffee taste is the most important thing to test. If a coffee maker produces a cup people like, it’s doing something right, regardless of how well the machine maintains certain “ideal” brewing parameters. However, we still took empirical measurements of various brew characteristics to see if there was any correlation between them and the top performing machines.

We ran the machines through seven rounds of blind taste tests. We spent our first day with Joe Coffee’s Christopher Malarick to help set up our initial tests and determine a good, consistent grind size that worked well across the range of machines (we used a commercial-style Bunn grinder on all the whole beans). He was also on hand for our first round of taste tests, helping us measure total dissolved solids (TDS) in all of the coffee we tested.

Then we spent our second day conducting tastings with Counter Culture Coffee’s Matt Banbury, making grind adjustments based on the initial TDS readings, hoping to bring the machines even more into an ideal TDS range. On both days, Serious Eats staffers, all coffee drinkers with varying degrees of coffee experience and know-how, joined in on the blind taste tests. We continued subsequent rounds of taste-testing with several other kinds of coffee using Serious Eats staff, and any other coffee drinkers we could grab, to rate each cup.

Throughout the tastings we kept the brew ratio consistent: 16 grams of tap water to 1 gram of coffee. What we changed, from round to round, was the kind of coffee. To cover a range of popular coffees brewed at home, we tested whole-bean Starbucks Sumatra dark roast; Peet’s house blend dark-roasted Latin American beans; a Mexico El Chango dark roast from Variety Cafe; Counter Culture Coffee’s Iridescent, a blend of Ethiopian, Kenyan, and Latin American coffee; and Joe Coffee’s Guatemala Hunapu microlot. We also used pre-ground, medium-roast Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, made with beans from Central and South America. We put paper filters—some required the cone-shaped version; others the commercial, basket-style filters—in each brewer. The panel evaluated samples, scoring each cup on a scale of one to five, with one being weakest and five being strongest, for acidity, body, and sweetness. Tasters also jotted down any additional qualitative notes they had for each cup.

After two rounds of blind tastings, the experts identified five machines as their favorites, each selecting a mix of less expensive brands, like the Braun, Black & Decker, and Mr. Coffee, and higher-end coffee makers, including Bonavita and Oxo. The experts’ picks didn’t overlap as they both selected entirely different machines. The other tasters agreed consistently on three of the five selections—they felt that the Black & Decker and Mr. Coffee made unbalanced coffee, with fainter aroma, and sharper taste. We continued our taste-testing, but later eliminated the Mr. Coffee, which took too long to evenly spray the grounds, and the Black & Decker, which had a design that spills water into the brew basket when the lid is open and the power is on.

One expert picked the Bonavita as one of his favorites (along with the short-lived picks of Mr. Coffee and Black & Decker), while the other selected the Braun and Oxo. All three machines did well throughout the rest of the taste tests, with the Bonavita and Braun eventually winning, and the Oxo making it to the penultimate round. Tasting with a variety of beans means the tasters were likely going to have different reactions to the coffee each time. But, switching the coffee was also effective in showing which machines performed well in the eyes (and mouths) of the greatest number of tasters.

Coffee made in the Breville, which initially was considered average by the experts and other tasters, started earning higher scores when we used lighter roasted beans. The coffee made in the Ninja was deemed by the experts to be over-extracted from the start (very possibly due to long brew time and high temperature), and other tasters agreed, but it also returned favorable notes for aroma and, as the field narrowed, the machine was identified as one of the favorites.

After subsequent tastings, weighing in the evaluations of the non-pro tasters, and some disqualifications, five machines distinguished themselves: the Bonavita, Braun, Oxo, Breville, and Ninja. With more tastings we decided two of the models, the Oxo and the Ninja, didn’t separate themselves enough from the pack.

Measuring Brewing Times

According to the SCAA, the recommended brew time for a good cup of coffee is at least four minutes, but no more than eight. But, Matt Banbury tends to aim for a total brew time between 2:45 and 4:30, and says, generally, darker roasted coffees need a shorter brew time. We started the test by running water (827 grams of it, which is about 3 1/2 cups) through the machines without coffee or filters, to get a baseline measurement of brew times. The machines won’t brew any faster than these times, and once you add coffee, they will definitely brew slower, given that grounds and the filter will impede the flow of water.

Brew time is more than just the inconvenience of waiting for a pot of coffee, it should also influence the taste. But, we couldn’t make a correlation between time and taste. The Technivorm was the fastest, finishing the cycle in under four minutes, but the coffee it makes didn’t win over many tasters. The Breville was the second fastest and it makes very good coffee. On the other hand, the Black & Decker was one of the slowest models, taking nearly nine minutes to move all the water, and made coffee about half the tasters enjoyed. All of our winners fell into the four- to seven-minute range.

Measuring Brewing Temperatures

To track how hot the water is when it meets the grounds we placed a pair of thermocouples near the surface of the grounds, and tracked the temperatures every five seconds during the brew cycle.

When the water temperature is on point, it should help pull coffee’s good flavors and aromas out of the beans and into your cup—a process called extraction. But water temperature alone isn’t enough to guarantee a flavorful extraction. Other variables include brew time, blooming phase, and water turbulence. And then there is the coffee itself: grind size, the quality of the beans, and nature of the roast, etc. Most pros agree that not all water temps are ideal for coffee brewing, but there isn’t a consensus about what the “best” temps are. Experts tend to be wary of any temperatures that are too low or too high, though exactly what the cut-off is is up for debate. Experts generally advise avoiding water that gets too close to boiling. On the flip side, water that isn’t hot enough can under-extract the beans.

There is a temperature range that is considered ideal, but experts don’t agree on what those temps are. The SCAA’s optimal range of water temperature, which they define as the temp of the water when it makes contact with the grounds, is between 197.6°F (92°C) and 204.8°F (96°C). The SCAA’s guidelines also recommend that those temperatures be maintained for the duration of the brew cycle.

We buried a pair of Thermoworks thermocouple wires in the brew baskets, positioning them near the top of the grounds, to record how hot the water is during brewing. We placed one in the center of the basket, with a second sensor closer to the edge. They fed their measurements to a Thermoworks ThermaQ Blue tracker that recorded readings every five seconds. We brewed each batch of coffee with 720 grams of water (about 3 cups) and 45 grams of coffee, trying to run the largest amount that would fit in all the machines.

Some machines didn’t make it to 197.6°F at all, let alone hold it for an extended period of time. So those must be bad coffee makers, right? Not so fast. The Braun maxed out at around 190°F (87.8°C) and held it for about 35 seconds, yet it still made coffee most tasters enjoyed. The Breville stayed in the zone for 60 seconds and the Bonavita for 110 seconds. While the Ninja spent about 150 seconds within the optimal temperature zone, it also ran the hottest, reaching 212°F (100°C), and spent nearly twice as long above 204.8°F, which may help explain why it made strong tasting, sometimes over-extracted coffee. On the other hand, the Technivorm spent most of the brew cycle in the ideal temperature range, yet the coffee it made was never identified by any of the tasters as their favorite cup.

In the end, a machine’s ability to hit or maintain a specific water temperature was not a strong indicator of whether it made good coffee.

Measuring the Total Dissolved Solids

Brewing coffee is all about taking what we want from the coffee bean and transferring it to the water. While it might oversimplify the complex nature of coffee extraction, measuring the amount of total dissolved solids (TDS) is a quick way to check if you’ve pulled more or less than the right amount of material from the coffee beans. Coffee experts use a refractometer to calculate the brew’s TDS, which we interpret as strength while drinking.

Many coffee professionals, and the SCAA, aim for a TDS between 1.15% and 1.35%. But there is good coffee outside of this range too. “We find that our coffees, and a lot of similarly light-medium roasted, high-quality coffees, taste great between 1.20% to 1.40%,” says Christopher Malarick. “The better the coffee, the higher up we can go, in theory, because the coffee has more to offer.”

During our testing we used TDS percentages to dial in a grind size that we could then use in all the machines, hopefully producing a TDS number within the acceptable range for every pot. In our first round of tests, the TDS percentages ranged from 1.30% to 1.71%. For subsequent rounds, we adjusted the commercial Bunn grinder to a coarser setting, trying to lower the TDS percentage. That worked to a degree, but as we changed to different beans, the TDS continued to jump around, sometimes going higher, sometimes going lower, demonstrating that, depending on the bean and the brewer, there is no one “perfect” grind size that will work with all these coffee makers. This goes to show that coffee is a moving target and fine-tuned adjustments are necessary to get the best cup, no matter what machine or brewing method you use.

This also highlights one limitation in our testing: To fairly and scientifically compare all of these machines, we needed to control as many variables as possible, settling on uniform grind sizes, ratios, and other factors in each test. But technically, we could have adjusted those variables to dial each machine into its own optimized range for any given bean. In the end, we decided to go with a more real-world scenario, trying to replicate what most people do at home, which rarely involves analyzing TDS or obsessively adjusting the grind with a high-quality burr grinder.

In theory, a person could take one of our losing machines and get a better cup out of it by modifying all the other brew variables, pulling the machine closer to its highest potential. But we also know that most folks at home don’t have the expertise or willingness to do this, which is why we feel that the machines that performed the best with a range of beans all ground to a pretty typical “drip” coarseness were, by definition, the best for most folks at home. But even our winners could be configured more precisely, or thrown out of whack, as bean choice, grind size, and the other variables change.

Checking The Brew Basket

A coffee maker should wet the brew basket consistently, and quickly. We took photos of the brewers every 30 seconds and disqualified poorly performing machines that took too long to spray the grounds.

To brew a good pot of coffee, the machine has to wet the grounds consistently, because you can’t extract flavor from beans if the showerhead doesn’t soak them. Ideally, the brew basket is evenly wet within the first minute of brewing. Coffee that doesn’t get wet until long into the brew cycle will only get partially extracted (or not at all, in the case of grounds left dry). We examined the brew baskets of the machines every 30 seconds to see how well each sprayed the grounds. We disqualified any machine that failed to wet all the coffee in an acceptable amount of time, unless the machine was performing well in the taste tests.

Surprisingly, the pricey Technivorm struggled with this test. It left a significant amount of coffee dry for much of the brew cycle, and by the end, there were still portions of the brew bed that never got wet. The Braun, despite making tasty coffee, needed 3:30 to completely wet the grounds.

Ease of Use and Features

We disqualified lids that featured this design: the absence of a water shut-off means the showerhead pumps water when the power is on and the lid is up, which ruined a few of our tests, and could wreck your brew too.

We took notes on how easy the machines are to use and clean. If you’ve loaded an automatic coffee maker in the past, these models will feel familiar. Many have flip-up lids that cover the water reservoir and/or the brew basket, meaning you’ll have to pull the brewer out from under upper cabinets to use them. While emptying the machines, we noticed a few design elements that make it hard for the pumps to clear all the water. The Breville has a pocket that holds about a tablespoon of water below the level of the pump. Left in the machine after a long weekend, that water could get funky and that probably isn’t going to help your coffee taste better.

What bugged us the most? Many of the less expensive machines share the same design flaw: they don’t have a water shut-off when the lid is open. Typically, these brewers fix the showerhead to the underside of the flip-up lid, so when the top is down, the sprayer is above the brew basket. Without a sensor to confirm the lid is closed, the water flows even if the lid is opened mid-brew or if the power button is pressed accidently while the lid is up (and the water tank is full). Some of these machines have a better design that redirects this water right back down into the reservoir when it happens, but others allow the water to spew from the showerhead. There isn’t really a danger of getting burned, but there is enough velocity to reach the brew basket, which is extremely annoying and can ruin a batch of coffee if you’re midway through setting it up. We disqualified machines with this flaw because, as we tested, it ruined a bunch of brew cycles.

How We Chose Our Winners

After sampling dozens and dozens of cups of coffee, we selected winners based on a combination of performance and ease of use.

The Best Simple Coffee Maker: Bonavita 8-Cup Carafe Coffee Brewer

What we liked: The SCAA-certified Bonavita has a solid reputation for making great coffee and it didn’t disappoint in our tests. The experts singled it out for making balanced cups of coffee. We tried it with and without the bloom phase, and it did well in both scenarios. The design is straightforward; there is only one switch (you hold that switch down for a few seconds to enter or exit the bloom mode). While you can’t set it to brew at a specific time, it was one of the faster machines to move water, clearing the reservoir in about five minutes, so you shouldn’t be waiting long for coffee.

What we didn’t like: Our biggest pet peeve with the Bonavita is a common one: The brew basket sits directly on top of the open carafe, so before you can pour a cup, you have to remove it completely. That leaves you with a wet, grounds-filled brew basket in-hand, forcing you to either dump out the grounds and clean it right away, or set it down somewhere (where it can dribble coffee). Only then can you access the carafe. While we would prefer a more common slide-in brew basket, we do have to acknowledge a silver lining here: The current design forces you to clean the machine promptly, making it less likely you’ll leave stale, spent grounds in the machine for hours on end.

The Best For Control Freaks: Breville Precision Brewer Thermal

What we liked: While the Breville is an advanced brewer, it’s also easy to use—you can make a basic pot of coffee with a couple of button clicks. For those who want to tweak settings, you can dial in the length of the bloom time, the temperature of the brew water, and the rate that water is applied. This was one of the most consistent machines we tested, both in terms of TDS figures (where it hovered around 1.4% across a range of beans and grind sizes) and also the small differences in the temperature of the brew bed, from the center to the edge. All tasters agreed it made coffee that was clean, well rounded, and with a nice aroma. In later testing, with dark-roasted coffee, we noticed it was a little watery, which could probably be resolved with a finer grind and/or different ratio of water to coffee. Like the Bonavita, the programmable, SCAA-certified Breville creates a uniformly wet brew basket, and it was the second fastest brewer we tested. While we didn’t use it, it has a setting for making cold-brewed coffee. With an adapter, you can also slide in a stand-alone, pour-over coffee brewer, like the Hario V60 or Kalita Wave, and have the Breville function as the water heater and dispenser.

What we didn’t like: Before you can start brewing, the machine’s sensor has to recognize that the carafe is in place, which it failed to do about half the time (forcing you to jiggle the jug). The water tank has a divot in the bottom that always holds on to about a tablespoon of water from the previous brew cycle. If you’re not going to use the machine for a while you’ll have to invert the entire rig over the sink to get rid of that slug of water (or break out the turkey baster).

The Best Budget Coffee Maker: Braun Brew Sense Drip Coffee Maker

What we liked: A surprise pick during testing, the Braun (which includes a programmable timer) earned favorable remarks in nearly every round of tasting, despite poor performance in the brew bed-wetting evaluation. Both pros called the Braun’s coffee balanced and other tasters tended to like its results as well, calling the coffee smooth and drinkable (though it did taste acidic when brewed with Mexican dark-roasted beans). The dashboard is clean and the flip-up lid design is easy to work with. There is a replaceable charcoal water filter in the water tank, which we appreciate. Unlike other models that share a similar water pump and showerhead build, the Braun diverts water back into the reservoir, not the brew basket, if you accidentally start it with the lid up.

What we didn’t like: There is no way to shut the hot plate off and the LCD display is on the small side.

The Competition

A few quick notes on the other coffee makers we tested:

- The Ninja Coffee Bar Brewer consistently brewed strong-tasting coffee that was flagged by our pros as over-extracted. If you need a single cup of coffee, or like to sip a travel mug during your commute, you’ll appreciate the Ninja’s specific options for those two sizes and ability to accommodate both vessels, after you dial in the grind size.

- The Technivorm Moccamaster was one of the fastest machines we tested and one of the easiest to use—it only has two switches. But, while Amazon reviews are overwhelmingly positive about this SCAA-certified brewer, the coffee it made earned merely mediocre ratings from both pro and amateur tasters and it routinely failed to wet the coffee grounds evenly and sufficiently.

- The Behmor is an SCAA-certified smart brewer that you control with your iOS or Android phone. This is a brainy brewer—you can set the bloom time, brew temperature, or pick programed brew cycles for popular brands of coffee—but only when you can get it to work. We had connectivity issues with our test kitchen’s WiFi, which you probably won’t have in your home’s secure network. When we were able to get it to work, it got mixed results from tasters. In theory, its level of customization would allow better brew results with lots of adjusting of brew variables, but we weren’t able to find out due to tech issues.

- The design of the SCAA-certified Kitchen Aid concerned us from the start. To fill the water tank you have to pour cups of liquid through a narrow slot in the back of the machine, making the first step in the coffee brewing process an already fraught one: There will be spills. Amazon reviewers complained about the design too. Some reported water that often leaked from the tank onto the countertop. This model was also the third slowest we tested, taking more than five minutes to heat up the water before pumping. However, tasters noted the coffee was balanced with mild acidity.

- The OXO On Barista made it to our final five brewers. Easy to load, the SCAA-certified Oxo starts heating and dispensing water after only 30 seconds, but in later rounds of tastings, testers noted the coffee lacked aroma and had a weak taste, which presumably could be resolved by tweaking some variables. Amazon reviews also cite weird glitches with the clock, which appears to reset itself. That might ruin your morning if you plan on waking up to hot coffee that brews on a timer.

- The Bunn Heat N’ Brew delivered weak, thin coffee from a brew bed that was inconsistently wet. While it has a simple dashboard, the LCD often blinked that the SCAA-certified coffee maker was still brewing even after the dripping stopped.

- The flip-up lids covering the water tank and brew basket on the Cuisinart Pour Over Coffee Brewer, which plagued a few of the machines we tested, makes it difficult to tuck the coffee maker under upper cabinets—a short power cord didn’t help things either. Tasters commented that coffee from this SCAA-certified machine was split between bitter or sweet, and balanced; others noticed an off smell with a lot of body that bordered on over-extracted.

- A top seller on Amazon, the Cuisinart 14-Cup Glass Carafe with Stainless Steel Handle Programmable Coffeemaker overflowed when we added our controlled amounts of water and coffee, which were within the brewer’s max fill levels. This is one of the coffee machines that spills water into the brew basket when the lid is up and the power is on.

- The Mr. Coffee scored high with one of our pros initially, but it fell short in subsequent taste tests and the brew basket never became fully saturated. Additional testing delivered coffee with a lot of acidity.

- Like the Mr. Coffee, the Black & Decker scored well with a coffee pro at first, even if the notes of Serious Eats staffers ranged from “unbalanced” to “nutty and rich.” The build is basic—one switch, no fancy clocks or presets—and while the machine will brew with the lid up, the water is diverted back into the reservoir, not the brew basket. The Black & Decker was the second slowest model we tested, taking nearly nine minutes to empty the water tank.

- The Hamilton Beach did well in initial tastings, but later panelists were as likely to describe the coffee as weak as they were to call it balanced. In the end, we disqualified it for its leaky lid design that does not include a water shut-off, but we appreciated the removable water tank and swing-out brew basket—both features save space under upper cabinets.

- We disqualified the Krups Savoy early on for brewing and saturating the filter basket with the lid up.

[ad_2]

Source link