[ad_1]

[Illustrations: Tram Nguyen]

Biscuits and Gravy–flavored Lay’s may have been the first bag of novelty potato chips I really hunted. I’m not going to say exactly how many stores I went to in search of a bag; all I’ll say is that it was more than one and fewer than five, and part of that sentence is a lie. I finally found them, quite by accident, on a family trip in the middle of Missouri. I bought a few bags. I won’t give you an exact number. Again, it was more than one and fewer than five. Again, part of that sentence is a lie.

Since then, I’ve searched big-box stores and pharmacies, sandwich shops and gas stations, looking to score potato chips that lay claim to the flavors of everything from chicken tikka masala to chicken and waffles. I sit down with a bag, a bottle of seltzer, and a notepad, and I take detailed tasting notes, as if a bag of Lay’s had a terroir. Sometimes, the flavors fizzle. When they pop, though, there is a shock of recognition, an alignment of idea and execution that amounts to a sort of magic, capable of inspiring a sense of childlike wonder. It’s like licking the wallpaper alongside Willy Wonka—the snozzberries really do taste like snozzberries.

Novelty potato chips walk a difficult path. Their task is not merely to taste like the thing, but to recall the Platonic ideal of the thing. Biscuits and Gravy potato chips ought not to taste like the biscuits and gravy I actually ate growing up, or the version you ate. Those versions might differ in myriad ways, and yet the chips must capture both, and all others as well. In order to succeed, a simple bag of chips must attain some quiddity, a –ness. Biscuits and Gravy–ness, Fried Green Tomato–ness, Crispy Taco–ness.

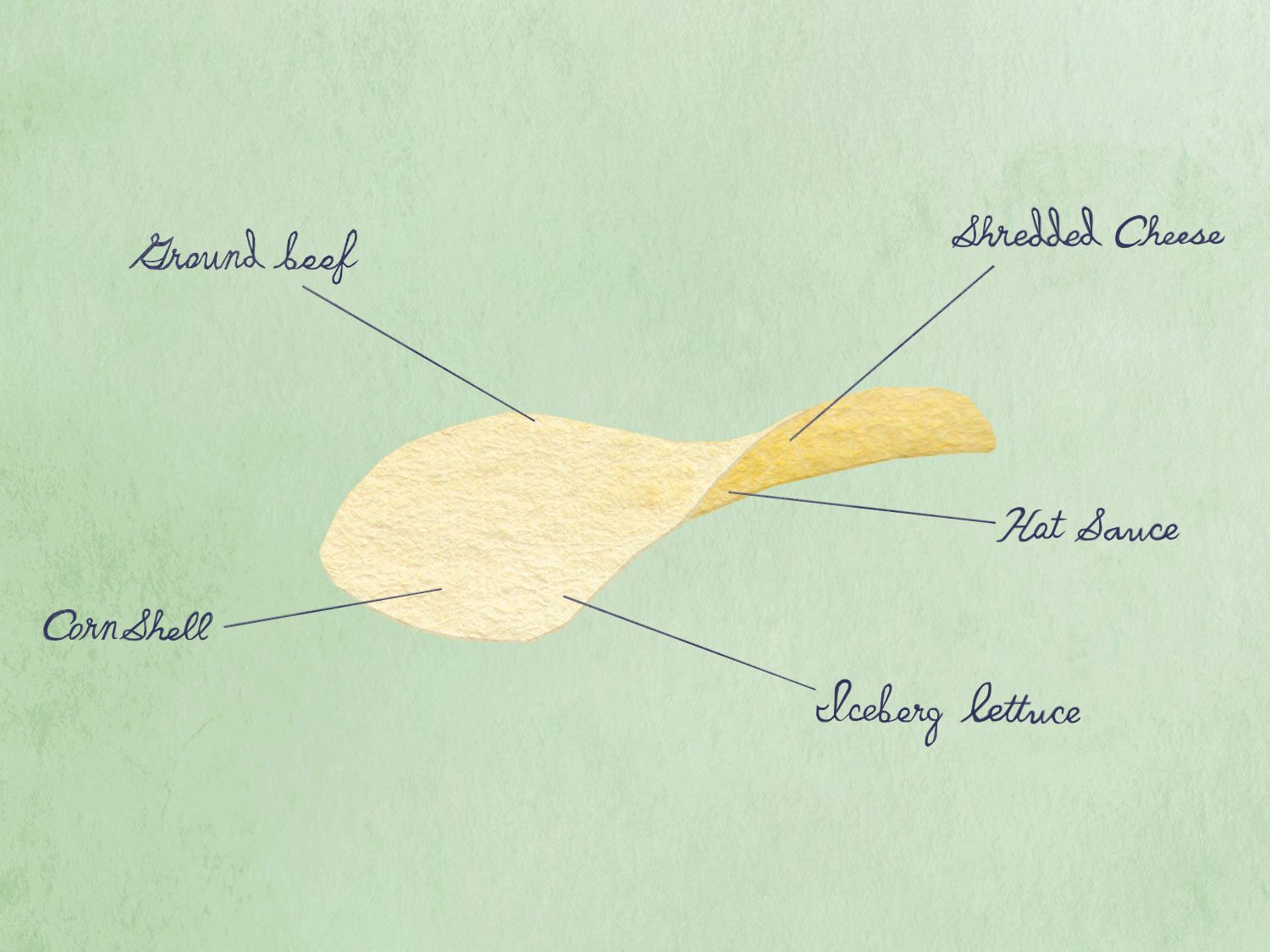

Those last two are among the newest crop of Lay’s novelties, rounded out by Everything Bagel With Cream Cheese, which isn’t worth your time. The Crispy Taco flavor, on the other hand, does everything a novelty potato chip flavor should do. The smell gets you first: It’s savory, filled with toasted corn and vague meat smells and the memory of the fourth-grade lunch line on Tuesdays. With novelty potato chips, the smell is often what gets you the most, like the spirit of the thing rising up and announcing itself directly in your brain. This is certainly true of other foods, but here, it can be a sort of bait-and-switch dividing line; the smell grabs you, the flavor shrugs you off. The best examples offer full olfactory embrace.

And that’s exactly the case with Crispy Taco Lay’s: the smell is a bear hug. And after that initial scented salvo, the individual, layered flavors of seasoned ground beef, crunchy corn shell, and prefab shredded cheese unfold in your mouth like Violet Beauregarde’s gum courses. “This is okay,” you think to yourself. “I can kind of see where they’re going with this, and it does taste kind of like a ta…”—and then it hits you, like a sucker punch to your sense memory: The strangely specific flavor of shredded, slightly oxidized iceberg lettuce rushes your sinus cavity, a bit of olfactory trickery that functions somewhat like a particularly effective Magic Eye poster. Holy shit, there’s a sailboat.

Of course, this phenomenon and its appeal are not limited to potato chips. Many of the currents of modern cuisine can be traced to the same sense of wonder, the same sense of discovery at finding that a thing is another thing entirely. Names like Adrià, Achatz, and Dufresne built legacies, at least in part, on the delight of unexpected recognition, the making of one thing into something else, and the toying with our ideas of flavor and of reality itself—Adrià’s spherified olives, Achatz and his edible campfires, Dufresne’s inside-out eggs Benedict.

If you’re not comfortable drawing a direct line between cappuccino-flavored snack foods and some of the greatest chefs in the world, then consider the humble jelly bean. I think it’s safe to say that if it weren’t for Jelly Belly, the jelly bean would occupy a space in the candy hierarchy just above licorice: esoteric, the favorites of oddball aunts and grandparents, but scorned by right-thinking children and adults. Instead, the humble bean occupies approximately 600 square feet of my neighborhood grocery store, where admirers load up on lever-released avalanches of Piña Colada– and Buttered Popcorn–flavored confections.

As with my beloved chips, the jellies are judged by the degree to which they capture the –ness of their subject. Even when they veer to extremes, dodging into the shock-factor territory of Potterverse flavor lotteries, the “success” of a flavor depends on uncanny likeness: Earwax-flavored beans that get the job done trump Earthworm-flavored beans that do not.

That said, one man’s Earthworm jelly bean is another man’s Crispy Taco potato chip. That’s why threading that needle, finding the right cues to recall a flavor for so many different palates and experiences, is key to the idea of novelty flavors in general.

This issue becomes even more apparent when you venture outside the idea of “mainstream American flavors.” When the snacking public has fewer samples for the flavor being attempted, the question of accuracy becomes murkier. Whose idea of “Chinese Szechuan Chicken” (vaguely offensive “Asian” font implied) becomes the defining flavor for a bag of potato chips marketed to a general American audience? If the chips manage to capture the numbing/tingling character that many consider to be the determinative element of the namesake cuisine, does that create Sichuan-ness, and for whom? Do diners raised on Americanized Chinese food determine the rubric for such a thing? Do novelty potato chips have to be “authentic”?

As with many things, the answer likely depends on perspective. The world of novelty chips is wide, weird, and wonderful. It extends far beyond the provincial bounds of a Kroger, even when that Kroger offers the highly sought-after Brazilian Picanha flavor. Oceanic treats that resonate for taste buds steeped in squid and shrimp paste might ring hollow for audiences predisposed to preferring flavors like Bacon Mac & Cheese or Mango Salsa, and vice versa. Beauty, as it were, is in the eye of the bag-holder.

Which brings us back to –ness, and to snozzberries. If you recall, none of the visitors to Wonka’s chocolate factory had ever tasted a snozzberry; they hadn’t even been aware of the existence of such a thing. The other wallpaper taste sensations played their parts and were well received, while the snozzberries get a salty response. In order for an ideal to resonate, it has to have been conceived of: You can explain a chair to someone who’s never sat, but you might find yourself hard-pressed to give them a concept of “chair-ness.” You can tell a man how to fry a green tomato, but you can’t convey to him the essence of “fried green tomatoes.”

I would argue that the essence of a food is a summation of sorts. A summation of all the fried green tomatoes you’ve ever eaten, yes, but also a summation of your thoughts about them. A summation of your memories of them, when and where you’ve cooked them, the people with whom you’ve eaten them. It is a personal history of taste and experience, and that is a powerful bit of magic indeed. It finds an echo in Sam Sifton’s wonderful and insightful Pizza Cognition Theory, but it’s developed over the entire span of your life.

It’s not just that first plate of biscuits and gravy that resonates in a well-tuned novelty chip. It’s the time you ate biscuits and gravy at your aunt and uncle’s place, before your uncle drove you through the central Texas hills on his Kawasaki, your 11-year-old heart beating through your chest. It’s the first time you made the dish on your own, scorching the roux a bit, but still proud. It’s the countless plates you’ve eaten at greasy spoons and fancy brunches, each one ranked and measured against the ones before, and serving as a measure in turn for the ones to come. It’s that, multiplied by everyone else who opens that bag, inhales deeply, crunches a chip, and sees a sailboat pop into view. It’s magic.

[ad_2]

Source link